About Us

Our History

In 1883, the first documented canal was dug to divert water from Tumalo Creek to surrounding farms and ranches to support crops and livestock. The system was formalized in 1902 when the Tumalo Project was organized as a state project for the irrigation of lands under provisions of the Carey Act. In 1922, the project was reorganized as an irrigation district under Oregon State laws and renamed the Tumalo Irrigation District.

Today, Tumalo Irrigation District manages two primary diversion sources: Tumalo Creek below Shevlin Park and the Deschutes River near Pioneer Park, in addition to Crescent Lake storage. The District serves 685 patrons, manages more than 80 miles of piped and open canals, and irrigates more than 7,400 acres growing hay, alfalfa, garlic, lavender and other cash crops. It also waters pastures for livestock and provides stock runs during the winter months.

The following outline is based upon Tumalo – Thirsty Land, by Martin Winch, published in six successive issues of the Oregon Historical Quarterly (vol. 84 no. 4 through vol. 87 no. 1). These issues are available online at JSTOR.org. Or you may now find the bound volume at the Deschutes Historical Society Library and the Barber Library at Central Oregon Community College. Thank you Martin for providing us with such a colorful and dramatic story!

The 1880s

- 1880 – First settlers begin dry farming in the southwest portion of the present District, on tracts acquired under the federal Homestead Act of 1862.

- 1883 – First documented ditch is dug to divert water from Tumalo Creek for farming.

- 1884 – First documented irrigation of Tumalo lands from Tumalo Creek, on the site known as Wimer Flat, where Tumalo Reservoir was later attempted.

- 1891 – 1899 – A series of development corporations file claims to the entire flow of Tumalo Creek for irrigation. Their estimates of the flow are highly optimistic (250 – 500 cfs), do not account for the seasonal variation in flow, greatly overestimate (30,000 – 60,000 acres) the area capable of being irrigated with the available flow, and greatly underestimate the transmission loss and the costs of an adequate canal and storage system. The principals in the earliest corporations are entrepreneurs and promoters from Prineville north to the Columbia. They are soon replaced with others who have connections to national railroad development interests and distant capital markets. Railroads are rumored to be coming south from the Columbia and east from the Willamette Valley. Many investors know even less about realities on the ground than the promoters. Railroads and irrigated agriculture will open up a new land to development, production and settlement.

The Early 1900s

- 1900 – The Three Sisters Irrigation Company claims to have completed a canal system sufficient to deliver Tumalo Creek water to 10,000 acres. The Columbia Southern Railroad reaches Shaniko, halfway from the Columbia River to Prineville. Expectations are high.

- 1901 – Oregon accepts the federal Carey Act (1894), whereby settlers can acquire 160 acres of arid land if they irrigate 20 acres. Oregon seeks to administer the Act in such a way that no public money will be spent. The State will give private irrigation developers a lien against the lands benefited by canals and reservoir systems. The private investors will raise the capital and take the risks (and the expected profit). The productivity of the irrigated land will pay for its “reclamation.”

- 1902 – The Columbia Southern Irrigation Company has acquired the rights to Tumalo Creek’s flow, and is selling $100,000 of capital stock. At the Company’s request and upon receiving a $348 fee from the Company, Oregon appoints the Company as the State’s agent with respect to development of 27,000 acres of arid land to be irrigated with Tumalo Creek. This land becomes the first “Selection List” in Oregon under the Carey Act. Oregon grants the Company a lien of $10/acre – the power to collect $277,000 from these public lands. The Company claims that 18,000 acres of this land are “tillable.” The Columbia Southern Railroad is affiliated with the Harriman (Union Pacific) empire, which promotes the Tumalo lands nationally as “profitable 80-acre homesteads” in “a great fruit region” with “an abundance of water” (1,200 cfs from Tumalo Creek in June). The sale price is 60 cents (dry land) to $15 (land with water delivered to it) per acre, plus the $10/acre lien. By the end of the year, the Columbia Southern Irrigation Company claims it has sold 9,000 acres and predicts 30,000 acres of Tumalo lands will be sold and under irrigation by 1904.

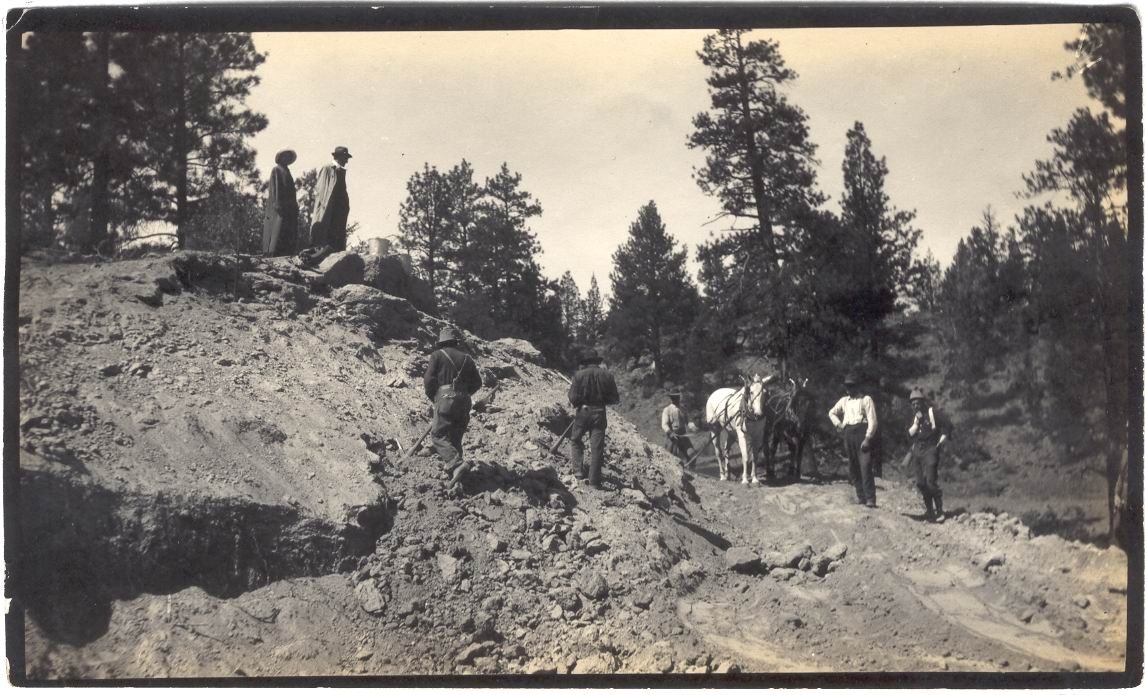

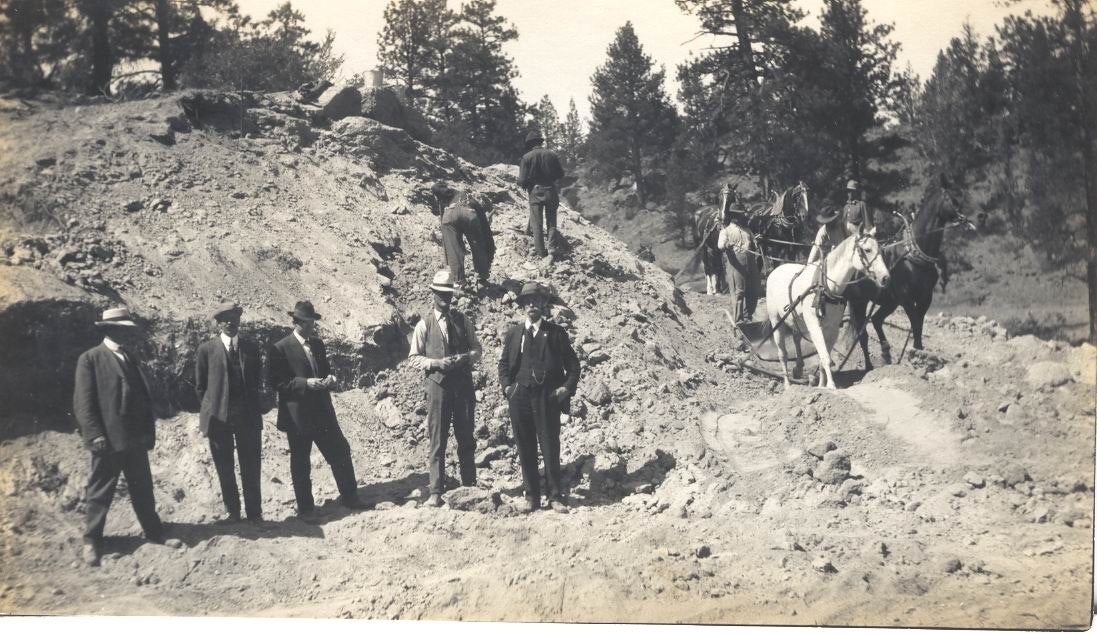

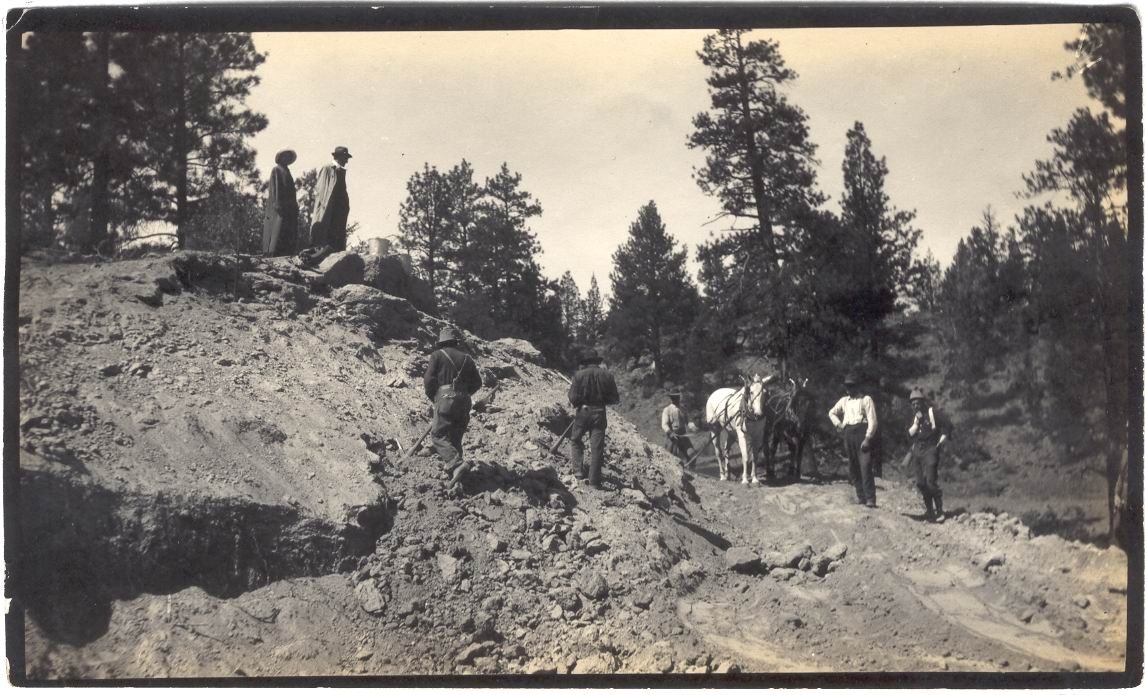

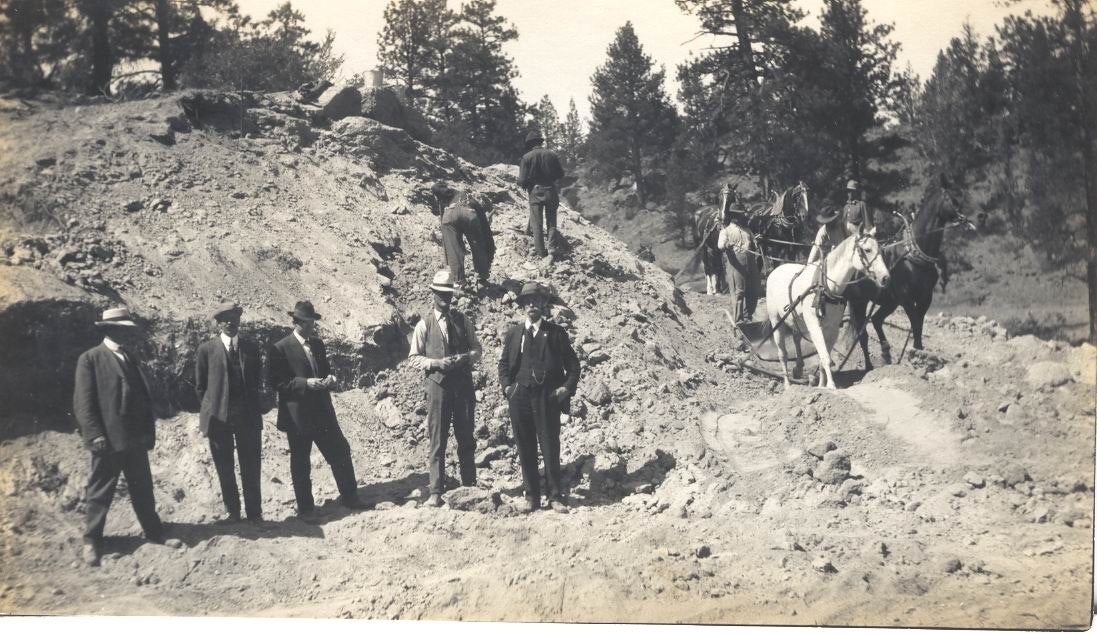

- 1903-1904 – The Company crew of 12 – 15 men with mules, horses, scrapers and shovels claims to have built 40 miles of canals. The national promotion of Tumalo lands peaks. The first settlers begin clearing land. Among the settlers, “opportunity seekers” outnumber farmers and few bring experience with farming high desert lands. A post office named “Tumalo” opens at Wimer Flat. The developers plat the town of “Laidlaw” (named by the resident Company partner after himself) at the present site of Tumalo, with the expectation that the railroads from the north and from the east will meet there, and mills will produce lumber and grain. Cline Falls and Plainview are platted. Bend is incorporated.

- 1905 – Oregon, relying on the Company as its “agent,” certifies to the federal government that 11,660 acres have been “furnished water sufficient to raise ordinary crops.” These Tumalo lands become Selection List No. 13, the first Carey Act lands to be patented to Oregon. The settlers discover that the first 1,000 acres to be irrigated have taken all of the water available; what will happen when the remaining 17,000 acres demand their water? And, there is no storage. The settlers form the West Side Water Users Association to get Oregon to come to their rescue. Oregon hires its first State Engineer. The Company sells out to a new development corporation.

- 1906-1909 – The Company has sold 15,000 acres as irrigable, and 2,500 acres are being irrigated. Laidlaw is bigger than Bend. Several of the early promoters go to jail. Battle is joined among the settlers, the Company, and the State – which enacts its first Water Code.

- 1910-1912 – The railroad from the north reaches Bend, bypassing Laidlaw. The settlers hang the Company’s resident partner in effigy and begin calling their town Tumalo, now increasingly overshadowed by Bend. Strong leadership emerges among the settlers and at the State, which assumes an increasingly active role. The Company fades.

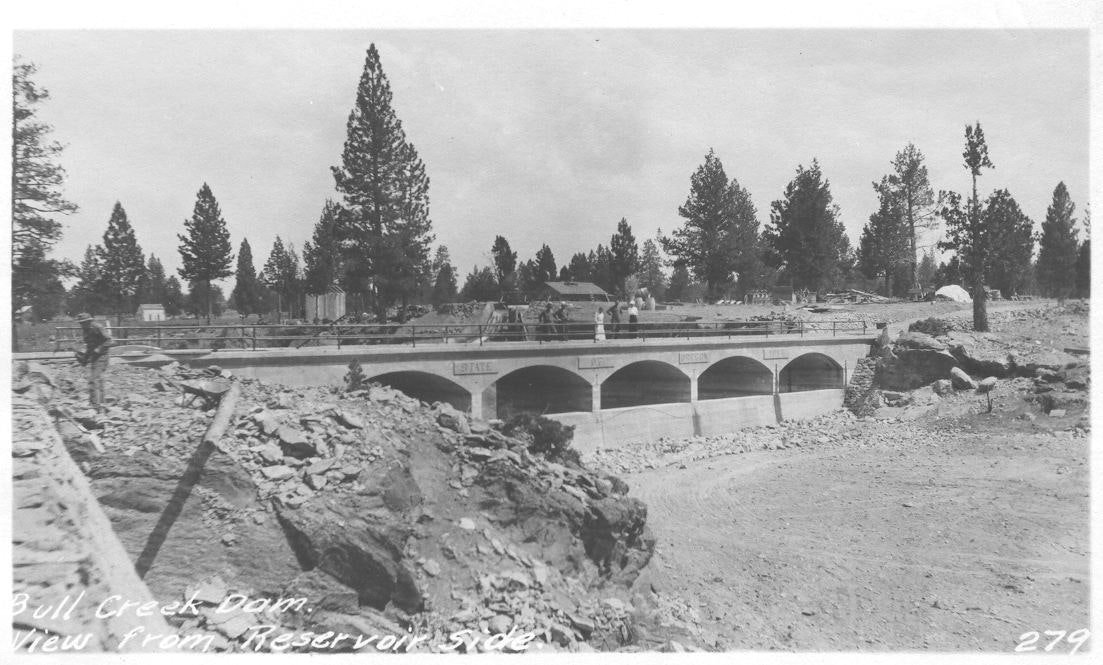

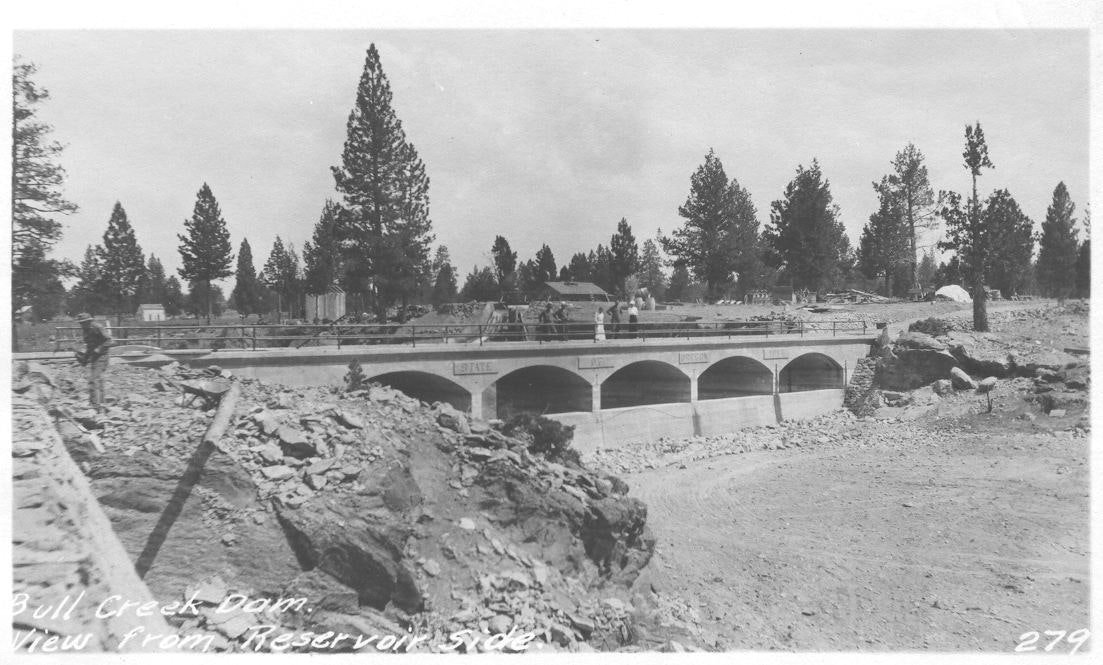

- 1913-1915 – The State Legislature passes the Columbia Southern Act, taking over the “Tumalo Project” and appropriating $450,000 to make it a success by building a reservoir at Wimer Flat and an improved and enlarged canal system with several wooden trestle flumes, to irrigate 22,500 acres. Expectations reach a new high. The project is completed within budget and on schedule, the dam holds, but Tumalo Reservoir fails to hold water.

- 1916-1925 – The Tumalo settlers, irrigating 5,000 acres, form the Tumalo Irrigation District. They believe they need more water, a right and a place to store water, and more settlers to help pay for improvements, operation and maintenance. They resist paying the State for its failed investment. They issue $650,000 in irrigation bonds, proposing to irrigate 15,000 acres. They buy a storage right on the Deschutes at Crescent Lake and build an impoundment structure. They build a diversion dam on the Deschutes at Bend and a canal with a wooden trestle flume crossing high above Tumalo Creek to feed their existing distribution system. They sponsor a “colonization” campaign, promoting the Tumalo lands as “Best in the West.”

- 1926-34 – The irrigation bond market and the colonization campaign fail. It is a period of extreme low flows on the Deschutes and Tumalo Creek. The first adjudication of the Deschutes recognizes 6,768 acres of Tumalo lands as beneficially irrigated, and allows for a transmission loss of 45% of the diverted flow. Bond interest and operation and maintenance assessments go unpaid. Would the District be better off at its 8,000 irrigated acres, or several times larger? A Bureau of Reclamation report recommends that “no government funds should be expended on or in behalf of” the Tumalo lands.

- 1935-53 – The Tumalo irrigation project is barely holding on. Neither the bondholders nor the State are repaid. Bend buys neglected farms and acquires the water rights, ultimately becoming the single largest holder of rights on Tumalo Creek. Some post-war settlement, growing national prosperity, and the advent of electricity and easier transportation afford the Tumalo lands a slowly increasing financial stability. However, the impoundment dam at Crescent Lake is failing, and trestle flumes on the main canals are deteriorating, threatening to dry up the Tumalo lands. Who will pay to rebuild the dam and the main canal structures? There are 92 farm units, the average unit with 72 irrigated acres; one-third of the farmers work 3 months or more a year at another job.

The Mid 1990s

- 1954-71 – The Bureau of Reclamation agrees to rebuild the dam at Crescent Lake, with each irrigated Tumalo acre obligated to repay within 40 years. Trestle flumes are failing, portions collapse and are patched together again. Water loss increases. A range of strategies is explored, including lining the failed Tumalo Reservoir and pumping from the Deschutes to bypass the canals and flumes. Tumalo landowners increasingly go to work off the land. Farm income is increasingly derived from livestock. The irrigated lands support an agricultural economy increasingly subsidized by non-farm income.

- 1972-? – There are 236 farm units, many with 5 or fewer acres of water right when the District goes to the Bureau of Reclamation with a plan to replace many, but not all failing structures on its canal system, and to line the leakiest canal sections. A proposal is again considered and rejected to enlarge the District, to 18,000 acres. The District proposes to repay $3.5 million over 40 years on a per-user fee rather than on acreage and the productivity of the land, and the Bureau agrees. Subdivision of irrigated lands continues. Residential densities increase along the open canal between Bend and the Tumalo lands. Tumalo water users reject a bond issue to replace remaining trestle flumes and much open canal with pipe. The District continues to struggle to finance improvement and maintenance of its distribution system.

Photo Gallery